Read an Excerpt of The Many Half-Lived Lives of Sam Sylvester

The first time I see the house, it’s as it swallows my father.

I count to three—Dad’s strategy for doing things I’m not ready to do—and make myself look up.

The sound of something rattling in a hastily packed box behind me has stopped. I’ve carefully kept my eyes on my phone, scrolling Tumblr, but I can’t avoid it anymore. I sit here watching motes of dust drift in the slanting afternoon light.

The front door is even ringed in red like a mouth. Not a bloodied mouth, nothing monstrous. Nor are the two dormer windows at the top in any way aggressive. They droop. The house looks like it tried but that it had found whatever it tried just too hard, and it quit.

I can kind of relate to that. New house. New city. New school.

Again.

I hope I do better than the house did.

“Sam!” Dad sticks his head out the door to holler. “You’ve gotta come see this place!”

He’s so excited about it. I’ve seen pictures, of course, but he insists they don’t do it justice.

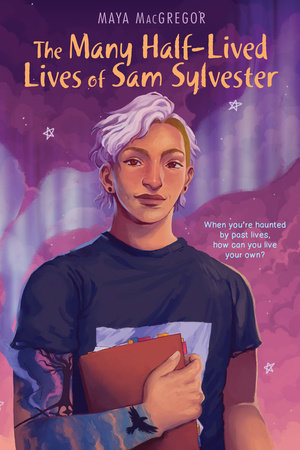

I push a lock of lavender-swirled hair out of my face and open the car door.

Outside the wind is chilly, and I’m amazed that I can smell the ocean. The salt tang to the air and the brisk winter wind wake me right up. I shouldn’t be surprised to smell the sea; it surrounds Astoria on all sides. There’s even a damn palm tree in the yard next door. Aren’t we fancy? I like it. There’s no one around, but it’s Wednesday afternoon, so I guess people are still at work. Just as I think it, I see a person with a backpack covered in She-Ra and Steven Universe patches and Pride flags turn the corner onto our new street. I’m pretty sure I feel their eyes on me as they look over their shoulder, and I hurriedly turn away, even though I want to know if I saw right—I thought I saw the telltale pink-purple- blue of the bi flag. I don’t want to get my hopes up. Maybe I didn’t see what I thought I did; it was just a glance. I’m used to being the only queer in the room (the only one who was out, anyway), and in Portland, I was still too terrified to even register that wasn’t true anymore.

Tapping my thumb against my iPhone’s screen, I trot up the few steps to the house. I close my eyes on the top step. The floors over the threshold are dark hardwood, maybe walnut. Even from here, I get a whiff of newish paint, the smell fading but not gone. The foyer’s mostly offset by pale light coming through the windows. The house is oriented north-south, and I wonder what it’ll be like in the golden hour if the sun ever really comes out here.

I can see it behind my eyes, all warm orange turning the dust motes to sparks instead of sparkles.

“Sam!” Dad calls my name again. He’s upstairs, from the sound of it.

I open my eyes and let the house swallow me too, stepping over the threshold.

The house echoes around my footsteps. It’s a strange sound, like I’m descending into a cave. We have zero furniture. There’s supposedly a truck from IKEA coming in the next day or so, but for now, my feet on the stairs feel heavy, so heavy their thumps should be heard by the ocean and its waves three streets away.

I put one hand on the banister as I climb the stairs, and my trepidation grows. Like the sea wind or a wave at the change of the tide, it washes over me and retreats, slipping back into the deep.

At the top of the stairs is Dad, leaning on the railing. He’s a smidge taller than I am, around six feet. I’m still not used to seeing him without his locs surrounding his warm brown face, always in contrast to my pale white skin and naturally dirty blond hair that is more half-hearted wave than Dad’s gorgeous tight coils. He cut the locs off for his new job. I said I didn’t want him to cut them. He said they were heavy and giving him migraines with extra pressure under his hard hat (plus his hairline’s receding, and he’s self-conscious about it), and then he chased me around the apartment after I buzzed his head. The downstairs neighbors pounded on their ceiling to tell us how much they appreciated that.

He laughed at the time, but I think Dad had more mixed feelings than he let on, and the silliness was him trying to hide it. He’s worn locs since I was little, and while I know it was his choice and his reasons, I think he felt the weight of more than hair once it was done.

“Did you see the palm tree?” I ask. It feels important that he knows it’s there. Palm trees are vacations and sun-drenched shores, and this move is neither of those things, but the tree seems hopeful anyway.

“I did, I did.” Dad grins at me. “Not quite a tropical paradise, but I thought you’d like it. Come see your room.”

I follow, trailing my hand along the banister. It looks like it’s been freshly sanded and re-varnished, the same dark wood as the floor. My fingertips stick slightly on the smooth surface. I think if I bent over, I could see my face in the glossy reflection.

He’s giving me the biggest room. He insisted that he’s too lazy to climb stairs to get to bed, and his smaller room has an en-suite, which just means he gets his own bathroom. And when I walk into my new room, a little shock goes through me.

The room is huge. The windowsill directly ahead of me spans both dormers, almost a window seat, and is a solid two feet deep. The upper bit rises straight along the outermost edges of the windows and then curves inward to meet in a little point like the peak on top of an ice-cream cone.

Walking to one of the walls, it’s almost too bright to look at. It’s white. White-white, not eggshell or cream. It looks and feels hastily done. There’s even a seam visible. Dad would be mortified if his crew did this. I rap my knuckles on it, and a hollow sound greets me.

When I touch the paint, I take a step backward, the way I saw a kid do once at the IGA supermarket when he called a woman Mom and when she turned around, it was a stranger. A thrill buzzes up the length of my spine, an echo of the premonition I hadn’t even articulated in thought enough to consider being right. Someone did cover something up here.

It’s not the sound of the hollow echo that startles me, but the feel of it. Like instead of wood, my knuckles touched an electric current—or the ghost of one. I fight the urge to pick at the seam, to dig into the wall to be able to touch whatever is waiting behind it.

“What do you think?” Dad gestures around with a flourish as I spin around to look at him. He had his back to me and must’ve missed my movement. “You’re going to be Emperor Sam up here.”

I rap my knuckles on the wall again, harder this time, trying to ignore the way it sends little shock waves zipping up and down my fingers. Yep, definitely hollow. I want in there. I can’t figure out what’s waiting if I can’t touch it, and this crappily done wall is in the way. Dad watches as I circle him, knocking on each wall. Sometimes I knock a few times, listening to the variations in sound. I find a rhythm. Hollow at hip level, fading into shallower sounds in both directions, then back out to hollow again. Dad doesn’t say anything. He’s used to me by now.

“You can be yourself here, kid,” Dad says.

I think he means what I’m doing right now—knocking on walls like the weirdo I am. I wonder if what he says is true. For one glorious moment, my universe expands like his words sparked a Big Bang. I could be me. Really me. For the first time. Maybe figure out who the hell that even is.

The moment contracts as quickly as it expanded. I pull my hand back, and I tap my fingernails hurriedly against my palm, stimming.

“There’re shelves behind the walls, I think,” I tell Dad.

He gives a little start at my words, then looks around. He’s used to me not responding to emotional things, too. Walking over, he knocks lightly on one panel, and sure enough, it gives that same hollow echo a little too deep for it to just be regular drywall and beams. Like I said.

“Huh,” he says.

He doesn’t question, but he does look at the wall a bit closer. He gives an offended sniff at the shoddy crafting of that wonky seam and mutters, “Previous owner’s attempt at DIY, maybe.” After a moment, he beams at me. “It’ll be a good project for us to open them up. If you want.”

He looks so eager that even if I didn’t want to, I’d agree. Besides, now that he’s seen that seam, I wouldn’t be surprised to wake up with him fixing it in the middle of the night. It’s going to drive him nuts.

I return his smile. “Damn right.”

“Don’t say damn.”

“Darn tootin’.”

“That’s worse. Say damn.”

His phone goes off downstairs, playing “The Imperial March” from Star Wars.

“Uh-oh. BRB.” He lopes out the door and thumps down the stairs calling at me, “Sam! No neighbors to yell at us now!”

“So you say!” I call back.

I haven’t seen him this happy in I don’t know how long.

I trail my hand around on the wall, feeling the uneven paint and that thrill just out of reach. My fingertips buzz against the paint like I’m touching one of those lightning balls you find at novelty shops. I can almost see where the drywall bows a bit between the shelves beneath it. There’s something there, something for me to find. And this room is mine.

New town, new house, even a seemingly new dad.

I hope to hell it goes better than last time.

. . .

I pass the time waiting for Dad to return by lying flat on my back in the middle of my new room, staring at the ceiling and trying not to scratch at my still-new sleeve tattoo. The tattoo was a deal when I turned eighteen. Dad said I could get one if I passed pre-calc, but I think it was also his way of giving me agency over my body after what happened in Montana. And I don’t think even Dad knows what it all means, the designs I chose, even though he went with me to all my consults and listened to me talk to the artist. I’m not even sure I know what all of it means. The top half from my shoulder to elbow is watercolor, the aurora borealis. Throughout the colors are black designs. A bird molting feathers that bleed into ink splotches. A constellation. A tree that becomes roots that become a fan of swords at the crook of my elbow. Elbow to wrist is more watercolor, but this time water-water, like colors of water. A raven swimming at my wrist, wings splayed. They’re all familiar images to me, even if they dissolve like the northern lights in the sky when I chase them. Trying to figure out weirdness is an ongoing thing in my life.

Like this room.

Something about the room unsettles me. Not in an Amityville way. Something . . . else.

Lying there alone, for a moment I’m suspended. It feels like this place wants something from me. Probably just my “vivid imagination,” or whatever my teachers called it before Dad got me my proper autism diagnosis. Or my histories, which my therapist in Missoula said were autism-related special interests. You know, like that show with the autistic kid who knows every single Pokémon. That’s not always what it looks like, obviously. We’re not all the same. For me it’s finding the stories of teens who died too young. Some of my tattoo is for them. That I can never tell Dad. I didn’t even want to tell my therapist; I just had to explain my histories started before the attack, not after, since she naturally assumed it was me almost dying that made me obsessed with teen deaths. Nope.

I swallow as the scar on my neck twinges.

Dad comes back so quietly even I don’t hear him until he scuffs his foot on the doorjamb. He stops in the doorway, and I meet his eyes without lifting my head from the floor. After a moment, he walks over. He lies down too, bumping the top of his head against the top of mine.

“Bad news,” he says.

“Was it the furniture people?”

“Yep.”

“Are they bringing us a stampede of un-potty- trained puppies?”

“Nope. How would that possibly be bad news?” Dad throws his hands in the air as if I’ve said something outrageous. “Stampeded by puppies is a life goal.”

“Puppies piss and shit all over, and not cute little poop emojis. But puppies are cute! And I guess hardwood’s easier to clean than carpet.”

“Sam,” Dad says, “practice not swearing before we go meet your principal tomorrow.”

“Fine, fine.” The floor is still nice and cool against my back. My hands explore it, palms down, fingers finding the cracks between the floorboards. “So what’s the real bad news?”

“Holiday season holdup. They’re coming a few days later.”

“So you’re saying we’ve got plenty of time to knock down some walls before they get here.”

I can feel his quiet chuckle because it shakes his head against mine.

“Yeah, that’s what I’m saying.” Dad’s quiet for a moment. “You still okay about the new school thing again?”

He says again because it’s the second one this year. It’s not a normal thing for us, moving.

This time I’m quiet, long enough for Dad to go, “Sam?”

“Yeah, I’m okay.” I mean, okay as I can be. I don’t need to say that out loud for him to know what I mean.

“The principal sounds very supportive,” he says. “And Oregon’s not Montana.”

“I know.”

I do know, but kids are kids and teenagers are teenagers, and that’s the same anywhere you go, especially these days when all sorts of ugly are ready to stamp all over our progress toward ever-elusive equality.

I feel it then, that tightness in my throat that comes with the mention of Montana. More than just my scar getting twitchy. My muscles tighten around my eye, and I don’t try to stop the movement in my face. It’s just me and Dad here. I ball my hands, pressing my nails into my palms in quick flutters.

Dad scrambles up behind me. I look at him upside down.

“Come on,” he says. “We’re gonna unload the car. And then we’re going to set up our egg crates and sleeping bags, and then we are going to go for a walk to see . . .” He pauses to stare at me melodramatically. “The ocean.”

I can’t help the small bounce I do. Dad is good at this. Giving me direction, expectations. Especially because tomorrow will be stressy, and even he can’t tell me how it’ll go.

Dad notices the bounce and grins wider. He has learned to tune himself to my frequency.

He keeps me busy for the rest of the day and into the night, and we explore Astoria from the stretch of sandy beaches and slate-gray water (I love the hypnotic sound of the waves, real waves, not just my white noise machine) to the small downtown with tourist shops that are sleepy and unrushed since it’s the off-season despite the Christmas lights everywhere.

By the time I lie down on my egg crate in the too-echoey room, I am actually exhausted enough to fall asleep immediately for once.

I don’t know how falling asleep is for the rest of the world, but for me, it’s like stepping into a tunnel of silver-white mist with the aurora behind it. That’s the one part of my tattoo I get in full. Colored lights flicker through this tunnel, and I’m here. I’m present. I know what lies beyond the mist, even if I can’t touch it. I can taste it.

Some nights, most nights, that’s all there is.

Not tonight.

I’m back in Airdrie, listening to my old principal tell Dad that they don’t have enough evidence to expel the kids, just like the cops said they didn’t have enough evidence to bring charges against them.

He says, “I’m sorry. It’s not as simple as accepting Sam’s word that she recognized the Barry boys and Sherilee Tanner. We need evidence.”

My dad is still, so still I can feel his fury. I can’t talk because my throat is swollen. I want to open my mouth and scream until my jaw unhinges and I can eat this principal whole. The way he says “the Barry boys” as if he’s not their uncle makes me want to vomit.

“This was a hate crime,” my dad says softly. “And you will use my child’s correct pronouns.”

Dad’s the only Black man in a white-as- a- blizzard town, and everything he does here is quiet, soft, because to everyone around us, his very existence is loud, even as the white folks here proclaim how they’re not racist. How could they be when they haven’t run our interracial family out of town and besides—and I’ve literally heard people say this—they can’t be racist when everyone is white, right? We stayed because Dad loved his mountains and his job; our ten acres in the foothills of the Sapphires were his sanctuary. Until they couldn’t be mine.

But Dad. His words hold the intensity of a supernova, and I love him for it. The principal’s mouth starts moving, but I don’t hear a word he says.

I’m seven years old again, and it’s the first time I ever see Dad. He comes into the foster home with the social workers, and when I see him, I know. He looks at me, and something ignites in me, something fierce and bright and everything at once. I know he doesn’t just see a ragged little white kid with shaggy dishwater hair who people think can’t talk.

He looks at me and my Led Zeppelin shirt and my hair in my face and he saves me. In that moment, something in his shoulders loosens, something in his face softens. He takes me out of that place and the first thing I ever say to him on my eighth birthday is thank you.

I’m sixteen, and I’m not Sam Sylvester. I reach for my name but I can’t find it, even though I think I should know it. It feels close, present like the scent of the sea in the wind and as unattainable. I’m surrounded by books and David Bowie’s voice and laughter that lightning-zings back and forth between me and someone I can’t quite see. They are backlit with the sun, the outline of curls the only clear thing in the haze. Golden light pours through double dormers, and the room is filled with hazy giggles that fade as soon as they began. I swallow and cough. And then that laughter turns to a gasp, my gasp. My throat is itchy and tight, and I fall to my knees and I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.

Light fades from my eyes into red and purple flashes.

. . .

“Sam! Breathe!”

I gasp a breath big enough to drain the room of air.

Dad has me, my arms crossed over my chest, holding me in a tight cocoon. The back of my head throbs. I gasp again. Then again.

“Hey, Sammy, it’s okay, it’s okay.” The hall light is on, cutting a golden swathe into my room.

I flail for a moment, my brain belatedly processing Dad’s words.

“Breathe in,” he says, and I do. “Breathe out.”

I do that too. He breathes with me. This is a ritual we’ve repeated far too often. This is why I will never understand how people think family is as common as blood. To me, family is breath; it’s trusting the person beside you to demand your right to air in a world that would take it from you. It’s the vulnerability of feeling someone’s chest move in a careful rhythm to give you your own back. Dad and I both know this fear for different reasons. His mom died of lung cancer when he was a kid.

Slowly, he releases his grip and lowers me to the floor. I’m all the way off my little egg crate pallet, and at first I think it’s the floor’s fault that my head’s throbbing, but then I see Dad wince and rub his cheekbone.

“Shit, D-Dad, your cheek.” Alarmed, I scramble to sitting position. My chest is still full of my rattling heartbeat. I try another slow breath.

“It’s okay, Sammy. I’ve had worse.” He waggles his tongue through the hole where his eye tooth was—it got knocked out before I was born, and he wears a plate during the day. “I’ll live.”

I swallow, trying to keep my heart from swinging on my uvula. This was worse than the other ones, and he knows it.

“What time is it?” I ask. The sky’s still dark, but that means nothing in December.

“No idea.” Dad sits back and leans on his hands while I check my phone.

“It’s five to seven,” I say.

“Do you want to talk about it?”

“The time?” This time I’m being purposely literal, but Dad doesn’t smile.

“Sam.”

I don’t answer.

“Okay,” Dad says, and with him, I know he means it. Some people say that to preface them changing tactics. Not Dad. “Want to see if we can find a decent breakfast place?”

I nod at him. Sweat drips between my shoulder blades, tickling. This time I help him up off the floor, and he mimes a broken back.

“Skull emoji,” I say wryly. “I’m going to shower. Meeting’s at nine, right? Do we have time?”

“Half past nine, and I hope so—be quick. I’ll meet you downstairs in thirty.”

I have to go downstairs myself to grab my toiletries and clean clothes. In the shower I wash quickly, scrubbing my face and throat as if I can wash away the dual-nightmares. One was me. Sam. I lived it last year.

I collect stories of kids who died before nineteen—when I was younger, that seemed like the threshold between childhood and adulthood. Kids who got sick, kids who got killed, kids whose own brains told them to die. I feel like someone should remember them.

That dream—that had to be the one from Astoria, from the eighties. Kid named Billy Clement, though I couldn’t recall his name in the dream. I try not to let myself think about him. It’s too weird.

My special interest happened before my attack. She used to tell me I was morbid, but I just thought somebody should know the stories of kids who don’t get to grow into adults. I thought they deserved to be seen the way Dad saw me.

I dress myself methodically. Black boxer briefs made of softest modal, a binder Dad had made special for me, tattery jeans, long silky tank top, long cowl-necked sweater with a jagged asymmetrical hem. Black eyeliner and a smudge of silver at the edges of my eyes. Dad insisted I get new things when we left Montana (I’m half-surprised he didn’t set my old stuff on fire). I did the shopping at thrift stores, but Portland had that market cornered. I think Dad was a little surprised at the direction I took, but looking like a badass makes me feel safer. I used to just wear old band T-shirts and jeans, but now every piece of cloth I put on my body is a choice. Girding myself in armor for the day.

I shop by touch before looks, but I’m good at finding the exact right thing. The softness of the sweater, the beaten-to- pliable texture of the denim, the intentional constriction of the binder— it’s all for me. No one else. I throw a little pomade onto my hair and toss it around until it waves the way I want it to, the lavender and pale green and silver-gray strands weaving together. They fall down over my right ear and expose the shaved left side of my head. I run my fingertips over the stubble, enjoying the sensation. Dad’s going to have to buzz it again soon on both sides and probably touch up the dye before school starts in January. He does construction management for a living, but I sometimes think he missed his calling as a hairdresser.

Dad finds us a diner and I get an enormous Belgian waffle covered in strawberries that are probably more sugar than fruit. Dad gets biscuits and gravy with a side of hash browns.

“Want some carbs with your carbs?” I ask him over the rockabilly music playing too loudly on the speakers.

“You’re one to talk.” He holds up his coffee mug, and I reach out with my orange juice. “To new beginnings.”

“To new beginnings,” I echo, clinking my glass against his mug.

Halfway through my waffles, I get that low-belly slip and remember what today’s about. Remembering my therapist telling me to pay attention to what I feel in my body, I let myself feel it for a moment, but all I really feel is silly. Is this anxiety? If Dad notices me poking at a strawberry with my fork, he doesn’t say anything. Eventually I choke the rest of my breakfast down, sopping up some liquified whipped cream with my last hunk of waffle.

I don’t want to do this again, this whole meet the principal thing.

This time Dad seems to sense it.

“If it doesn’t work out here, we’ll work something else out for your senior year.”

My head jerks up from where I’m staring at my smeared plate. “What?”

“If public school is too much, we’ll figure something out. Homeschool or something. You could probably even pass your GED if you needed to, but I’d rather we try for your diploma. That’ll make things easier for you in the long run.”

Holy—“ Dad.” I stop. What’s that thing he always says? “We’ll cross that bridge when the Pope—”

“—Don’t finish that one.” His smile’s only half-wattage, but he stopped me from saying shits in the woods out loud. “I just wanted you to know it’s on my mind.”