A Q&A with Dan Bernstrom on Black History Month

As the father of five children ranging in age from 1-9, what are some favorite traditions for celebrating Black History Month in your family?

Black History Month is a dedicated time for our family to memorialize our past. For many Black families, this history was either erased or inaccessible. Also, when I use the word Black, I’m talking about my slave ancestry, those who cannot trace their heritage back to any specific African country, tribe, or culture, as well as those with African immigrant heritage. So what are our Black History Month traditions?

We go to the local library, check out a big bunch of books on Black culture and history. This could include anything from the Jim Crow laws and Brown vs. the Board of Education to the teachings of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Black Lives Matter. My eight- and nine-year-olds are readers. They read books at the supper table, and then we talk while we eat, sometimes about difficult topics such as oppression and segregation or whatever their books are about. I am thankful that most of these difficult topics are handled so deftly and eloquently in books. How do we find books? We look for notable lists or ask the local librarian. We also have books we return to over and over again, including Pink and Say, The Snowy Day, or Corduroy: books that point to the fulfillment of Dr. King’s Dream.

Next, we feast! We celebrate with Soul Food, such as fried chicken, macaroni and cheese, and short ribs, just as one might eat a hotdog, hamburger, baked beans, and potato chips for the 4th of July. Is this healthy food? No. Frankly, we need to ask why this food isn’t healthy. If you were a slave or deliberately impoverished and therefore had to eat scraps or leftovers from your master’s table, you would eat to survive, but you’d also make the best of it. Black families learned how to take bits of this and that and make it stretch, giving them the energy to last through long, hard days of work on little to no wages. Yet, even though some of these foods were born from suffering, like many things in the Black community, they are seasoned with love and lots of joy. And oh, do they taste good! So once a week, we buy take-out, or we cook some traditional Black Soul Food! And because religion and God have played such an important role in Black history, from Negro spirituals to the Black pastors who led the Civil Rights Movement, we feast on Sunday: like many Black families do after church. This is our tentative Soul Food Sunday Menu calendar:

February 5th: sweet tea, fried chicken (or Jamaican Jerk Chicken), creamy mashed

potatoes, Southern macaroni and cheese, collard greens, and sweet potato pie!

February 12th: sweet tea, short ribs, sweet potato casserole, collared greens, Southern

peach cobbler

February 19th: sweet tea, gumbo, candied yams, Southern tea cakes

February 26th: sweet tea, shrimp and grits, potato salad, banana or bread pudding

Every Friday or Saturday, we watch joyful movies with Black heroes. We also want to point our children toward possibility and racial unity. Here is the list we will choose from this year:

Of course, Black history should be celebrated every day of the year, but have you found in your life that having a month in the year dedicated to a focus on your history to be a blessing, a curse, or a little bit of both—especially as your children have grown and become more aware of the world around them?

I see Black History Month as an extended holiday and reminder that we have not reached the promised land yet, where milk and honey flow equally to all. It’s a month to renew our vows to the blind Lady Justice and tireless Lady Liberty. To acknowledge our pain (so we can forgive) or acknowledge our complicity (so we can say once again, “never again”). It is well documented that Judaism, Islam, and Christianity have greatly influenced Black culture. The Jewish tradition celebrates several feasts a year to commemorate their history and Law. The feasts last several days and often tell the story of hope born from suffering. In Islam, the month of Ramadan is a time where families focus on their relationship with God and one another. There is fasting from dawn until sunset, but there is joyful feasting at night. In Christianity, the high churches celebrate the four weeks of Advent, expectantly waiting for the coming of God on Christmas day. Black History Month is a special time of year in my family, a month of another type of Advent, with stories and food and reflection. How I wish more people would join me in my celebration. Maybe one day they will.

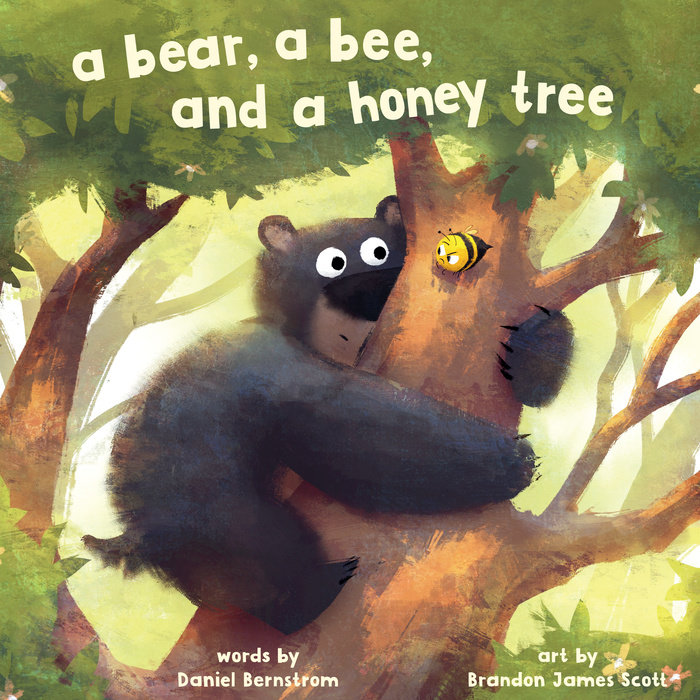

You have written a number of picture books featuring beautiful Black characters—some funny and folksy and other more serious and stirring–and then there is one about a bear and a bee and the honey they fight over. How was it different publishing Song in the City vs. publishing A Bear, a Bee, and a Honey Tree? Both books were published this past fall. Has it been pointed out that Bear, Bee it is your first picture book that doesn’t feature a brown-skinned child?

No one has pointed out that this is my first book without people. However, my book A Bear, a Bee, and a Honey Tree is inspired by my culture and lived experience. For example, I wrote the book because my son struggled to read, just as I did when I was little. I was a Black kid being passed along. I was a failing Black child. Had my mother not sent me to a new school when I was seven years-old, I doubt I would be a writer today.

There is an organization in Washington, D.C., called An Open Book Foundation. They purchased A Bear, a Bee, and a Honey Tree and gifted it to four or five entire classrooms! That meant every kid got that book. After a virtual reading of my book, the kids said thank you. They held up my book and pointed to their favorite page. Imagine over a hundred black and brown kids holding up a book written by a brown kid who failed first grade because he could not read. I didn’t know what to say. I fought back tears. Seeing all those kids holding up my book and pointing to their favorite page made me realize that I had accomplished what I had always longed to do, inviting kids who were just like me into the joy of reading. Color and culture are printed on the soul of the artist. It doesn’t matter if the book is about a blind brown girl sharing her song with others (Song in the City) or a book about a bear in search of something he longs to have but is just out of reach (A Bear, a Bee, and a Honey Tree), they are both sprinkled with cultural seasonings that are unique to the writer. That’s what makes any good book special.

As a poet and a writer, you consistently lean into rhythm and rhyme. Can you share some favorite lines of poetry written by Black poets—whether funny, meaningful, or particularly well-crafted?

A poet who is often overlooked is the formalist master Paul Laurence Dunbar. Here, he writes in Black English, but he does it in perfect meter and rhyme while telling a story at the same time!

Genius! This is his poem, “In the Morning”:

‘LIAS! ‘Lias! Bless de Lawd!

Don’ you know de day’s erbroad?

Ef you don’ git up, you scamp,

Dey’ll be trouble in dis camp.

Tink I gwine to let you sleep

W’ile I meks yo’ boa’d an’ keep?

Dat’s a putty howdy-do-

Don’ you hyeah me, ‘Lias -you?

Bet ef I come crost dis flo’

You won’ fin’ no time to sno’

Daylight all a-shinin’ in

W’ile you sleep -w’y hit’s a sin!

Aint de can’le-light enough

To bu’n out widout a snuff,

But you go de mo’nin’ thoo

Bu’nin’ up de daylight too?

‘Lias, don’ you hyeah me call?

No use tu’nin’ to’ds de wall;

I kin hyeah dat mattuss squeak;

Don’ you hyeah me w’en I speak?

Dis hyeah clock done struck off six-

Ca’line, bring me dem ah sticks!

Oh, you down, suh; huh, you down-

Look hyeah, don’ you daih to frown.

Ma’ch yo’se’f an wash yo’ face,

Don’ you splattah all de place;

I got somep’n else to do,

‘Sides jes’ cleanin’ aftah you.

Tek dat comb an’ fix yo’ haid!-

Looks jes’ lak a feddah baid.

Look hyeah, boy, I let you see

You sha’ n’t roll yo’ eyes at me.

Come hyeah; bring me dat ah strap!

Boy, I’ll whup you ‘twell you drap;

You done felt yo’se’f too strong,

An’ you sholy got me wrong.

Set down at dat table thaih;

Jes’ you whimpah ef you daih!

Evah mo’nin’ on dis place,

Seem lak I mus’ lose my grace.

Fol’ yo’ han’s an’ bow yo’ haid-

Wait ontwell de blessin’ ‘s said;

‘Lawd, have mussy on ouah souls-‘

(Don’ you daih to tech dem rolls-)

‘Bless de food we gwine to eat-‘

(You set still -I see yo’ feet;

You jes’ try dat trick agin!)

‘Gin us peace an’ joy. Amen!’