Why We Still Need Fairy Tales

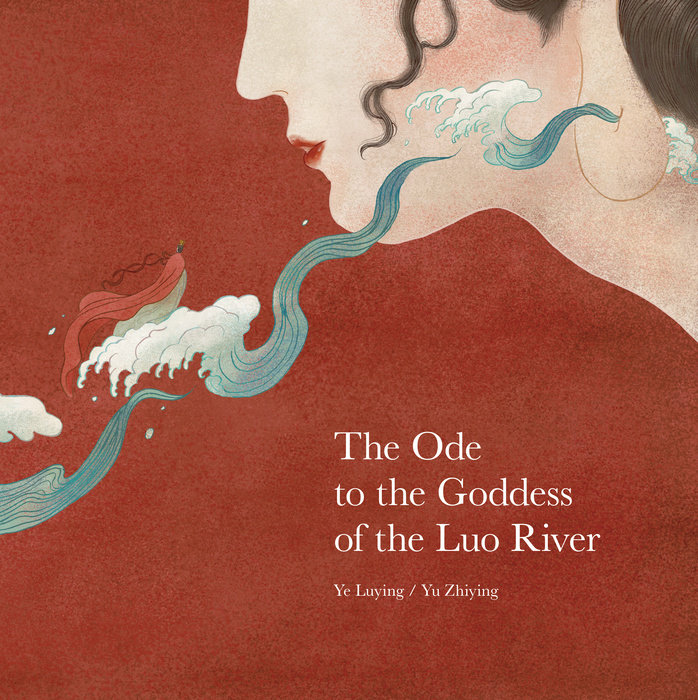

Fairy tales are wonder tales, dreamlike stories that feed our curiosity and address our most deep-seated wishes and fears. Children need them for the same reason they need to ask big, meaty questions. Questions like: Why do people die? Why doesn’t the sky fall down? and How did the world begin? Fairy tales have something to say on all these mind-boggling topics. While some good children’s books satisfy with stories about everyday happenings like a puppy’s hijinks or the loss of a tooth, fairy tales aim for a larger view. Rather than zoom in close on mundane specifics, they hold out an open invitation to imagine, “What if?”–providing chances for reflection that children in our stressed-out, over-detailed world probably need more than ever.

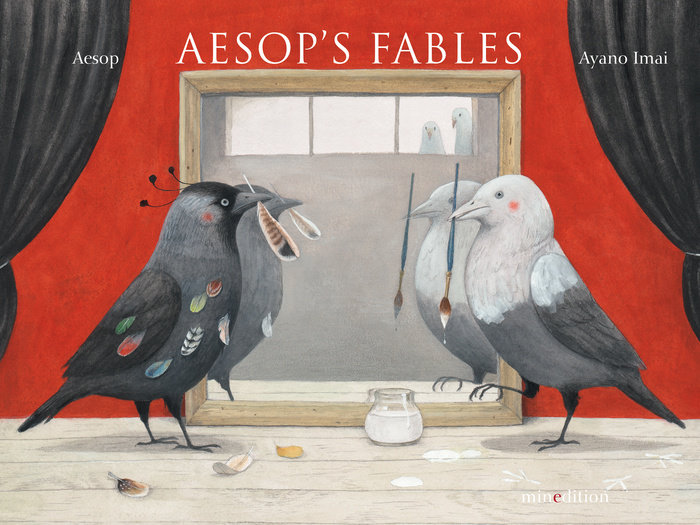

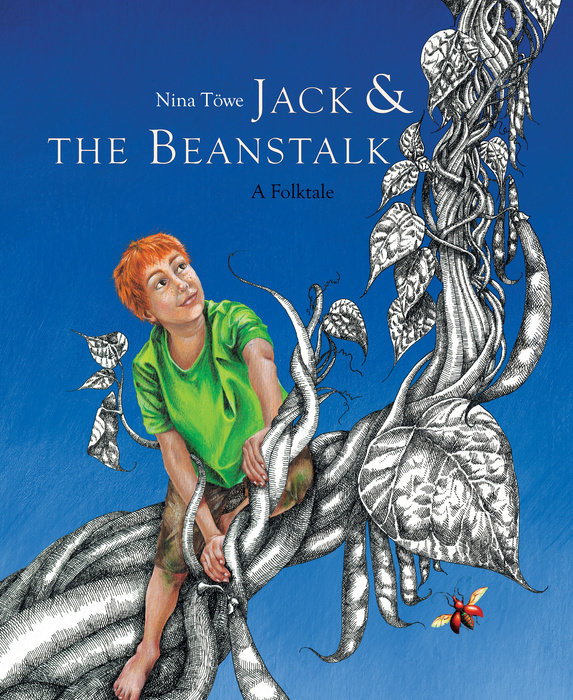

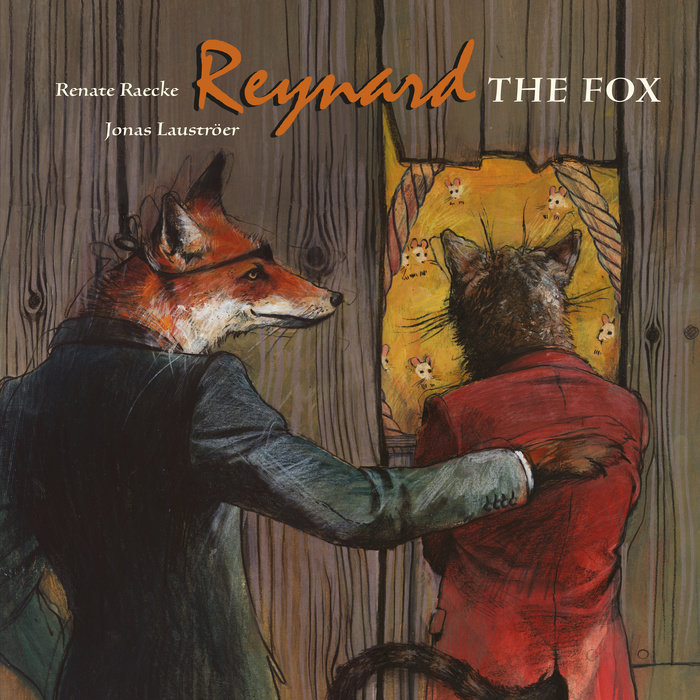

Fairy tales, like fables and myths, are a very old kind of storytelling that started as part of an oral tradition and morphed into literature. Nothing bland or half-baked ever happens in a fairy tale. Oftentimes, the impossible becomes the imaginable in the blink of an eye. If the hero’s next-door neighbor isn’t a royal, he or she is apt to be an ogre or goblin or a talking fish with magical powers.

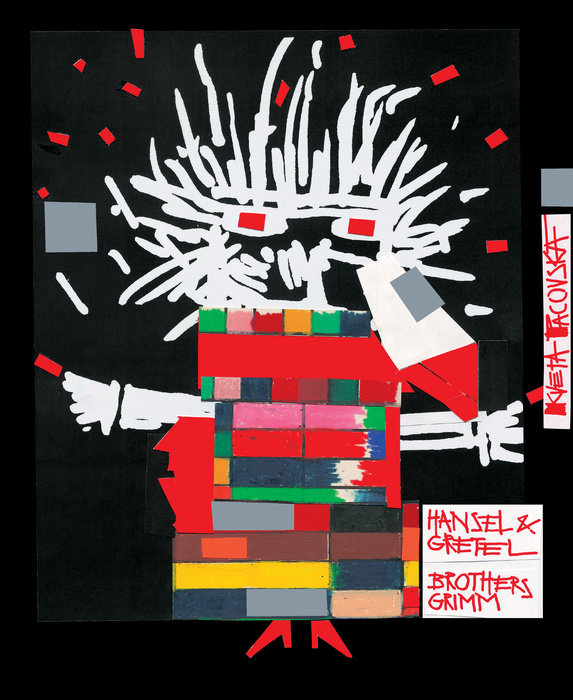

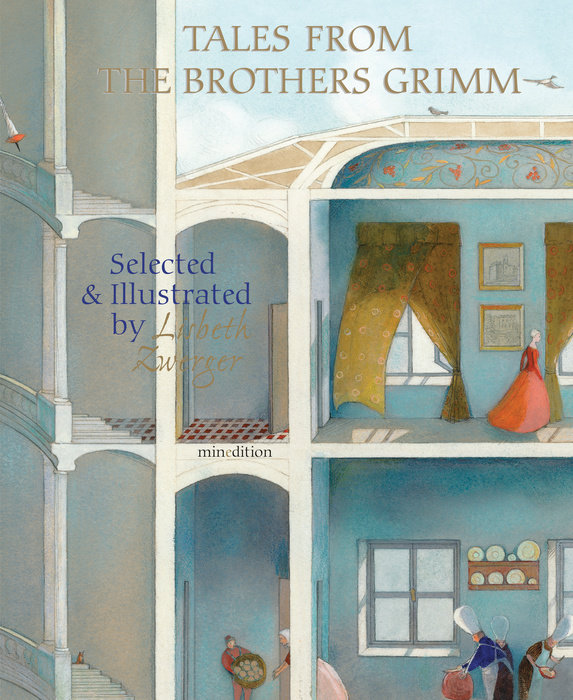

Consider one of the best known of all such stories. The Brothers Grimm–Jacob and Wilhelm, two German author-scholars–first popularized “Hansel and Gretel” more than two centuries ago. You’ll recall that a young brother and sister are left in a forest to die by their desperately poor parents, and that as they wander deeper into the woods the pair have a bone-chilling encounter with a witch. On the face of it, it’s an ultra-dark and not very relatable scenario; why then share it with kids?

One good reason for doing so is that, as psychologists have recognized, all children experience the fear of abandonment by their parents at one time or another. So, from a child’s perspective, the emotional core of the story is in fact quite real, and the wildly unreal parts actually make it easier for them to look their own fear square in the eye from a safe distance. A second reason is the deeply reassuring note on which “Hansel and Gretel” ends. It concludes with the two children out-witting–and destroying–their nemesis, then making their way out of the woods on their own power. Their happy ending is the realization they have taken good care of themselves; the story shows other children in turn a basic truth about the goal and meaning of growing up.

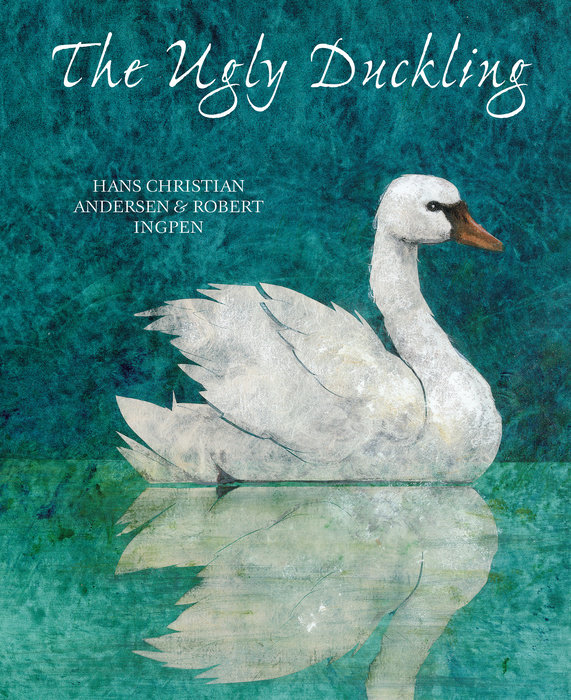

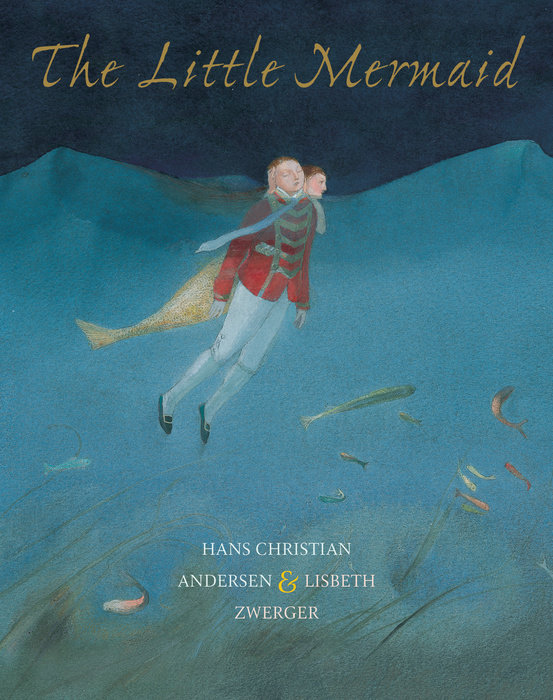

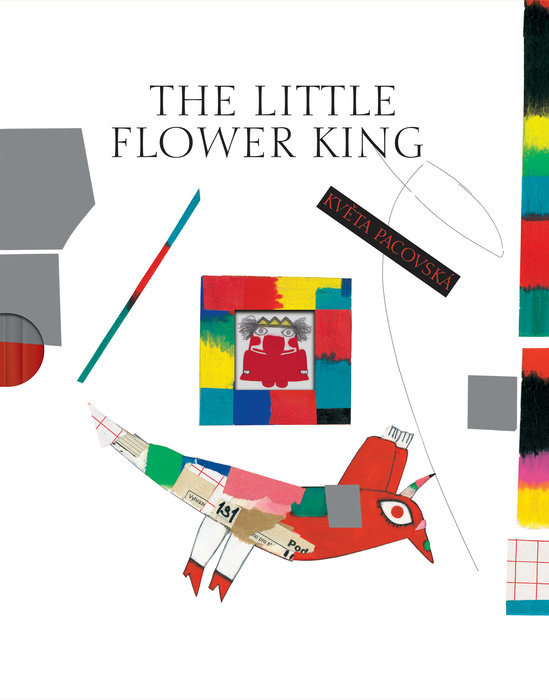

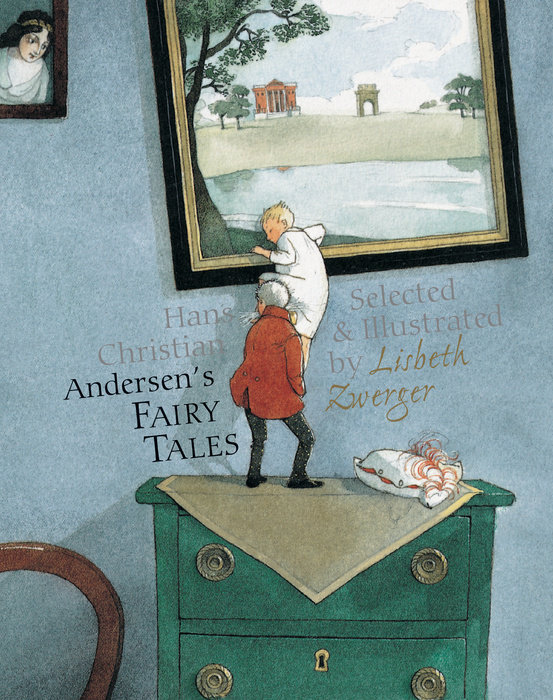

Or take a closer look at Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale “The Ugly Duckling.” Drawing on memories of his own painfully awkward grammar school years, Andersen homes in on some of the most common worries that gnaw at children from the moment they first step out into the world of their peers: the fear of standing out and not fitting in; the fear of not being good or good-looking enough. Andersen’s cruel, unfeeling duckling characters are classic bullies. By presenting these bad actors as barnyard animals, “The Ugly Duckling” beguiles as fantasy even as it pulls no punches about the consequences of disappointing human behavior. It works on both levels, freeing children to connect with it in whichever way suits them best. Children take what they need from a wonder tale like Andersen’s and simply forget or ignore the rest. It’s this same openness to multiple readings that has made fairy tales so alluring to illustrators from George Cruikshank and Arthur Rackham to Maurice Sendak, Robert Ingpen, and Lisbeth Zwerger–not to mention Walt Disney and the creators of many an opera and ballet.

As you might imagine, not all fairy tales have stood up equally well over time. Feminist critics, for instance, have rightly noted that Cinderella never gains real control over her own destiny; and that the story’s suggestion that a girl should wait for her prince to come is hardly a positive message for today’s world. The good news is that bookstores and libraries have a vast trove of the old stories to choose from, often in superbly illustrated editions designed especially for children; and that from version to version the stories continue to evolve and change. As Italo Calvino, the chronicler of Italy’s classic fairy tale tradition, has observed: “The tale is not beautiful unless something is added to it.” So, next time you and your child have a go at “Rumpelstiltskin” or “Little Red Riding Hood,” take a moment to ask each other what part of the story you might tell differently. Why let the Brothers Grimm have all the fun? Over to you!

—Leonard S. Marcus